INTRODUCTION

Asthma and COPD are prevalent chronic respiratory diseases driven by complex interactions between intrinsic and extrinsic factors that result in a wide spectrum of clinical presentations.1–4 Despite clear differences in their aetiology and pathophysiology,5,6 differentiating asthma and COPD at a diagnostic level is often challenging, particularly as analyses of patient spirometry data and inflammatory markers frequently identify obstructive airway disease phenotypes that encompass a mix of asthma and COPD features.7,8 Presently, this patient group is referred to as patients with asthma-COPD overlap (ACO).9,10 Individuals with ACO have increased disease severity,11 poorer quality of life12 and incur higher healthcare costs when compared with patients with asthma or COPD alone.13 GOLD_GINA guidelines defines as persistent airflow limitation with several features of asthma and several features of COPD. Considering the defect of enough data about its mechanism and phenotypes exact definition is impossible actually.14 Asthma is considered as a risk factor of COPD development. (Severe and lasted asthma with airways remodeling develops COPD).15–17 Patients with ACOS have more disease progression rate, morbidity, mortality, respiratory symptoms and exacerbation attacks than patients with asthma or COPD alone.18–21 Some features of ACOS are listed in the following flowchart22:

ACOS also may affect smokers without previous or current asthma that develops as chronic airflow obstruction in eosinophilic background.23 Patients with COPD and very positive bronchodilator test (>400 mL)is very possible to have some features of asthma and categorized as ACOS.24 Differentiating ACOS from COPD has been considered important, as it affects the choice of therapy, i.e. the use of inhaled glucocorticoids. Differentiating ACOS from asthma, however, has received less attention, even though there are options of targeted treatment for COPD, such as long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) and roflumilast. Furthermore, ACOS is presently a phenotype with heterogenic and poorly defined clinical features. For this reason, there is an urgent need for the identification of specific characteristics and biomarkers of ACOS.25 Regarding to review of available data, most of studies about obstructive pulmonary disease excluded ACOS subjects, so little information about this entity is available and current study aimed to compare therapeutic response between asthma and COPD and ACOS subjects through spirometric data.

METHOD

This cross-sectional study included 30 known patients with asthma, 30 known patients with COPD and 30 known patients with ACOS according to GOLD_GINA criteria, who refer to pulmonology clinics at Tabriz. The patients were included if they had good cooperation and mild to moderate severity of disease according to GOLD_GINA guidelines. A patient with effective treatment for malignancy, infection, or cardiovascular disease was excluded.

We assessed demographic (age, sex, …) and spirometric (post bronchodilator fev1 and fev1/fvc) parameters in all patients. The severity of asthma and ACOS was defined based on GINA guideline and severity of COPD was defined based on GOLD guideline. Spirometry was performed for all patients, then they took standard treatment regimen for 2 months according to GOLD_GINA , and after this period spirometry was repeated. Changes of fev1 and fev1/fvc was recorded.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data analysis was conducted by Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 26. Continous data were presented as mean and standard deviation and the categorical and nominal data were reported as number and percentages.

A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

A total of 90 obstructive pulmonary disease with the mean age of 57.74 ± 14.32 were enrolled in this study and 12 person of them didn’t complete follow-up. About 66.7% of patients were male and 73.1% had moderate severity according to GOLD_GINA guidelines.

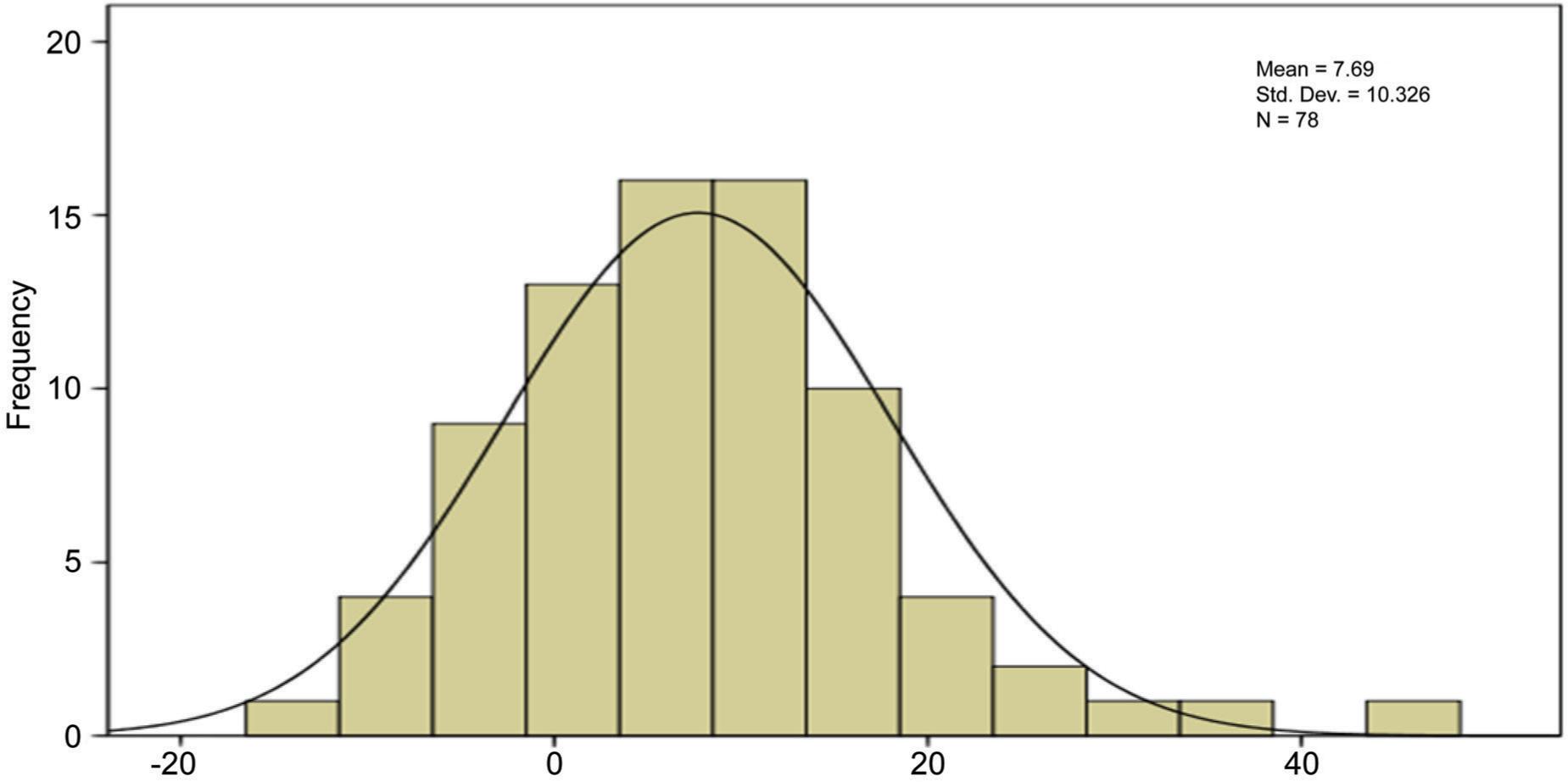

Table 1 reports the FEV1/FVC changesFEV1/FVC increases significantly more in Asmathic patients following treatment than in ACOS patients and least in COPD patients.

TABLE 1. FEV1/FVC changes.

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. error | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.49 | 0.093 | 0.602 | |

| Sex | −2.047 | 2.750 | 0.459 | |

| Disease | COPD | −7.558 | 3.097 | 0.017 |

| ACOS | −6.959 | 3.112 | 0.028 | |

Asthma = Reference group.

FIG 1. Increasment of FEV1/FVC percentage.

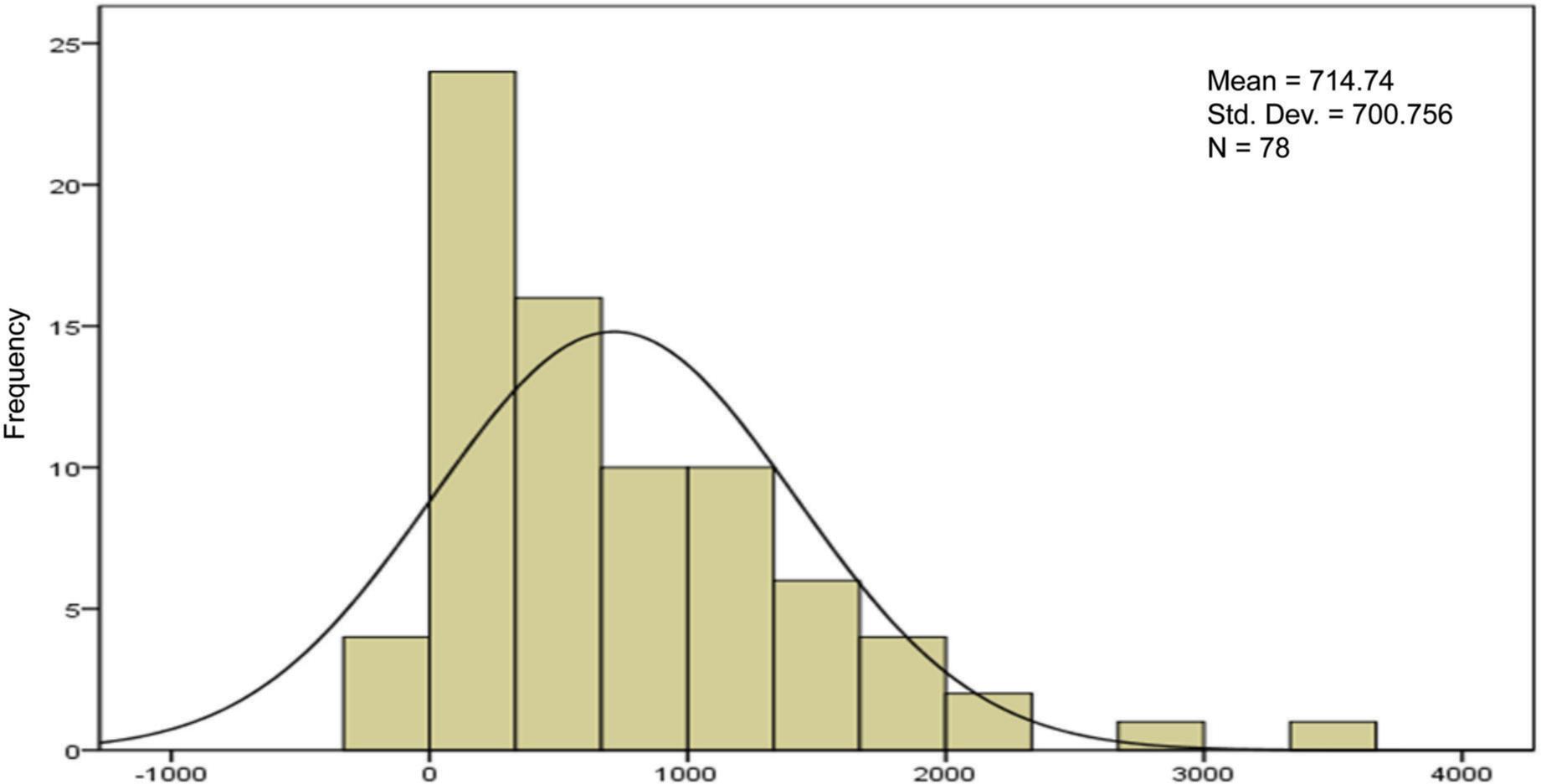

FIG 2. FEV1 changes.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to evaluate the differences of therapeutic response to standard treatment on base of spirometric finding in three groups of patients include asthma, COPD and ACOS. Totally Fev1 changes in response to treatment did not differ significantly between three groups (p > 0.05) but fev1/fvc changes differed significantly and this parameter in asthma was more than ACOS and in COPD was least. Considering FEV1/FVC changes, the spirometric symbolized therapeutic response in asthma was higher than that of ACOS, and the same was true for ACOS than COPD. ACOS may represent approximately 25% of COPD patients and nearly 20% of asthma patients. In primary COPD diagnosed patients identification of ACOS has therapeutic implication because the asthmatic component should be treated with inhaled corticosteroids that is only recommendation in COPD patients who suffer from recurrent exacerbations or have fev1/fvc<50%.26,27 So, what is the harm in treating a patient with COPD and suspected (but unconfirmed) or historical (and no longer clinically relevant) asthma with an Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)? It has been suggested that the main reason for diagnosing concomitant asthma in patients with COPD is to identify those who are likely to have a better response to ICS.28 According to defect of enough information about diagnosis and therapeutic response of ACOS, current study aimed to compare therapeutic response between asthma, COPD and ACOS by evaluation of changes of fev1 and fev1/fvc. This type of research has never been attempted before, based on all available data. In a previous study evaluating the reversibility of the airway after 12 years of active treatment for asthma, patients with ACOS had significantly higher fev1 and fvc results. Our results indicate that changes in fev1 in response to treatment did not differ significantly between three groups. But changes of fev1/fvc differed significantly between 3 groups (p < 0.05), and this parameter was greater in asthma than ACOS and in ACOS was more than COPD.

In previous study that performed by Tommola et al at Sinajoki respiratory department between 1999 and 2013 aimed to compare ACOS and adult onset asthma showed that reversibility in response to treatment in ACOS was more than asthmatic subjects, that is incompatible with our results.29 Some previous studies compared decline in pulmonary function between asthma, COPD and ACOS and have not observed significant differences in the rate of decline of fev1 between three groups.27

CONCLUSION

Our results indicated the significant higher level of therapeutic response in asthma compared to ACOS and this parameter in ACOS was significantly more than COPD on the base on spirometric findings. There for use of ICS in treatment of ACOS might be effective for clinical improvement in comparison to COPD patients, however there is no definite available data about ACOS. For a patient with COPD, a diagnosis of concomitant asthma had better thoroughly considered and based on an individualized assessment – in order to weigh up the benefits and risks of treating the individual with ICS. However, considering the limitation of the study, use of another tools for monitoring disease include the assessment of frequency and severity of symptoms, inflammatory markers and airway hyper responsiveness, and cohort investigations are needed with a higher sample size to approve this preliminary results.